How to scale Green Materials: 7 steps from Lab to Site

Identifying a pathway for low carbon material adoption

Thanks to everyone who has contributed, helped or provided introductions over the course of this article. While there are too many to thank, I’d like to call out the team at Zacua Ventures and Aaron Toppston over at GS Futures who were incredibly gracious with kicking off introductions for this piece.

The goal of this article is to expedite the adoption process for green materials and is based on conversations with over 40 industry experts, founders and investors. As such the tone is informative and action orientated. If you have anything to add, please feel free to email me.

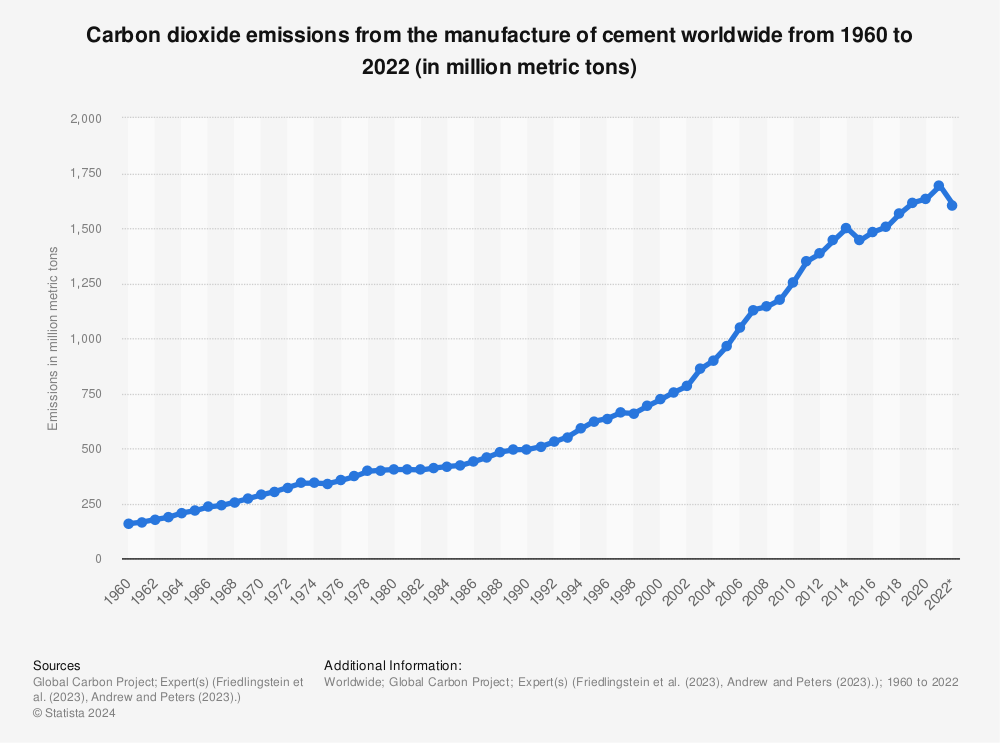

The building and construction industry is one of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases. In total it accounts for 37% of global emissions with building materials such as cement often highlighted as a contributing factor. Due to this and government climate targets, the industry is being forced to change and adopt lower carbon or ‘green’ materials in construction.

The challenge is that the green material industry is still nascent and fraught with risk. The solutions are often unknown and untested beyond the lab and this lack of performance data often means that clients and contractors are unwilling to trial them. Material failure can lead to costly delays, reputational damage and impact winning future work.

This market dynamic requires startups to be strategic in how they go to market, balancing the need to quickly generate revenue to extend their runway with the industries need for long term, in-situ data to validate reliability and performance.

The goal of this article is to expedite this process by outlining a series of steps or a ‘pathway’ which green material startups can learn from to help guide their go to market process and move from the lab to site. It’s based on interviews with over 40 startup founders, investors and industry experts on approaches they’ve seen work and considerations for scalability.

The audience is three fold:

Founders navigating selling their green material to the industry.

Corporates exploring opportunities for adopting green materials on projects.

Investors who want to support their portfolio companies and understand the sector.

Contents

Rising regulatory pressure for Green Materials

The challenge with adopting new materials in construction

Introducing the Green Material Pathway

Step 1: Determine your market entry point

Case Study 1: Pretred

Step 2: Become code compliant

Step 3: Get an Environmental Product Disclosure

Step 4: Get Commercial Insurance

Step 5: Choosing the right customers / partners

Step 6: Piloting

Proof of Concept pilot

Proof of Value pilot

Case Study 2: Xframes

Step 7: Scaling your commercial facility

Reading time: 20 mins

Rising regulatory pressure for green materials

Governments around the world are seeking to mandate the use of green materials on projects. The challenge is that the industry is nascent and so to foster investment and development, they are setting future emission targets and outlining green procurement rules.

Some key legislation in this sector is:

Buy Clean California Act (2017)

This act targets the emissions related to the production of structural steel, concrete reinforcing steel, flat glass and insulation. When these materials are used in public works projects they must have a Global Warming Potential (GWP) less than directed by the Department of General Services.Federal Buy Clean Initiative (2021)

In 2021 the US government, the largest domestic buyer of construction materials launched the Federal Sustainability Plan to achieve net-zero emissions procurement by 2050. This led to the Federal Buy Clean Initiative which prioritizes lower carbon construction materials in Federally funded projects.IRA Low Embodied Carbon material requirements (2023)

In 2023, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) developed low embodied carbon material requirements which are being actively used on 150 Inflation Reduction Act funded projects. This applies to the purchase of four key construction materials: concrete (and cement), asphalt, steel, and glass.Construction Productions Regulation (CPR) (Updated: 2024)

In 2024 the EU updated the CPR which sets standardized safety, performance and environmental impact requirements for construction products. The change introduces mandatory environmental reporting on factors such as CO2 emissions and energy usage for building materials, initially focusing on concrete, steel and insulation materials. Standards for these initial categories are expected by 2026.

A key insight here is from the CPR. Once the EU has created mandatory environmental reporting standards, these will be used to set caps / limits on emissions for construction materials (as the Buy Clean California Act does). Given the rate of development, it is possible that standards for materials will have mandatory limits for emissions by the end of the decade.

Despite this growing interest and regulatory momentum, the widespread adoption of lower-carbon or green materials remains limited. Why is that?

The challenge with adopting new materials in construction

The construction industry is characterized by both vertical and horizontal fragmentation, with stakeholders specializing in specific stages of the process.

As Brian Potter of Construction Physics explains: “A building is built by many different firms working together, each one handling a small aspect of the overall process. The plumbing contractor installs the plumbing, the mechanical contractor installs the HVAC, etc.”

This fragmentation creates challenges for the adoption of new solutions, as they often impact multiple stakeholders across the value chain, many of whom may lack incentives to embrace change.

For example, consider the value chain for low-carbon cement:

The Building Owner doesn’t directly buy cement, they’re buying a completed building.

The General Contractor (GC) purchases concrete from a Subcontractor.

The Concrete Subcontractor pours concrete sourced from a Ready Mix Supplier who buys the cement.

If they were to use a low carbon cement, it would impact all four stakeholders in some of the following ways:

The Building Owner must be willing to absorb higher costs, as green materials are often more expensive due to their lack of commercial scale.

The General Contractor must collaborate with designers and prepare submittals to ensure the mix meets specifications (as they are not using a traditional mix), a cost in both time and labor.

The Concrete Subcontractor may need to adjust handling and placing procedures, requiring additional training and resources.

The Ready Mix Supplier must ensure their production facility can accommodate low-carbon cement, which could necessitate facility upgrades or investments.

So how can startups navigate this complex stakeholder environment?

Introducing the Green Material Pathway

This pathway provides a series of steps which startups can follow to increase their chances of adoption. These recommendations are drawn from challenges faced by other startups during the adoption process and the strategies they used to overcome them. The goal is to help startups proactively address stakeholder concerns and streamline their journey to commercial scale.

The steps are:

Determine your market entry point

Identify low risk use cases where your material can be adopted without additional regulatory approvals.Get Code compliance

Collaborate with the International Code Council for expedited building code approval.Get an Environmental Product Disclosure (EPD)

Quantify environmental data about your product's life cycle to support regulatory reporting requirements for clients.Get Commercial insurance

Partner with brokers who specialize in insuring innovative materials to mitigate risks for general contractors / asset owners during pilot projects.Choosing the right customers / partners

Focus on working with ‘True Innovators’. These are construction firms that are willing to collaborate as you test and scale your product.Undertaking Pilots

Proof of Concept Pilot

Validate your unique selling point in real-world conditions on-site.Proof of Value Pilot

Develop scalable operational processes and establish best practices for adoption across multiple projects.

Scaling your commercial facility

De-risk your investment and secure project financing to support commercial-scale production.

Step 1: Determine your market entry point

Startups must identify an initial target sector to begin selling their product. As an unproven and untested solution outside of a lab environment, finding a customer willing to take on risk is essential.

A framework for identifying the right target sector includes the following questions:

Is the proposed application low risk?

Does the sector have low regulatory barriers for new products?

Does the customer have a high willingness to pay or require large volumes?

By carefully selecting the right target sector, startups are able to begin deploying their material and collecting in-situ performance data to refine their product. This data is critical for scaling and for convincing commercial or enterprise-level customers of the product's reliability and performance.

To illustrate this process in action, let’s examine a case study.

Case Study: Pretred

Pretred is a startup which produces sustainable barriers and barricades, made from 95% waste tires, and are an environmentally friendly and green alternative to concrete barriers.

The opportunity they identified was to replace concrete barriers on high speed / highway roads. However, this sector poses significant barriers to entry for startups due to strict regulatory requirements, including extensive crash and safety testing. Additionally, startups must demonstrate in-situ performance data and have manufacturing capabilities to meet large-scale supply demands.

To overcome this, they identified their initial market entry point as off road applications such as pedestrian delineation, perimeter control and parking.

These use cases are lower risk. For example parking barriers have less regulatory hurdles as the design speed is lower vs a highway.

By focusing initially on these use cases where there is low regulation, low risk, high volumes required and high willingness to pay (state department of transport’s have emissions targets and budgets), Pretred are able to to earn revenue, scale their production volume and iterate and improve their product based on client requirements.

Once reliability was established in off-road applications, Pretred began to move upstream to relatively higher risk applications (with larger TAM) as they have in-situ data and validation of their product.

This can be seen by the application’s listed on their website which showcases how they are going to market.

Pretred targeted low-speed roads as their second market segment. These roads have fewer regulatory challenges than high-speed highways but still provide valuable in-situ data and performance validation (as of Q1 2025, they are delivering their product for low-speed roads).

This increased demand and revenue allowed them to invest in scaling their commercial facilities to deliver for a larger market.

Now, with validated performance data, case studies, and scaled production facilities, Pretred plans to enter the high-speed road sector, the segment with the largest total addressable market (TAM).

This incremental approach allows Pretred to:

Systematically validate safety and reliability at increasing levels of risk.

Scale commercial production gradually in alignment with revenue growth.

Develop expertise in Department of Transport / client approval processes to streamline future compliance.

By the time they target high-speed highways, Pretred will have the operational experience, regulatory approvals, and production capacity necessary to support large-scale deployments confidently.

Case Study lessons for corporates

Corporates can effectively collaborate with early-stage green material startups by identifying low-risk entry points within their projects. These activities provide an opportunity to pilot innovative solutions while contributing to decarbonization targets.

Examples include:

Using low-carbon cement for all curbs in a low-speed residential area.

Trialing sustainable timber in non-structural applications.

Starting with these manageable applications allows corporates to test performance, build confidence and gather in-situ data without disrupting critical project timelines or introducing significant risk. Additionally they can showcase to clients their expertise in adopting new green materials.

Case Study lessons for investors

When evaluating green material startups for investment, investors should focus on:

Identifying the Market Opportunity (TAM)

Understanding the Market Entry Point

These factors help investors assess:

Time to Market

How long it will take for the startup to achieve commercial scale.Capital Intensity

The level of investment required to reach commercial scale.

This assessment ensures alignment between the startup's commercialization timeline and the investor's fund lifecycle.

For example if a startup requires 5 years to commercialize, but the investor is already 4 years into a 10-year fund, the investment may not be feasible.

Step 2: Get Code Compliance

To pilot test your product you need to prove that your product complies with the building code / standards. This is a set of rules which specify the standard for construction objects such as buildings or structures.

The code varies across geographies. For example New Zealand may have a code which has earthquake load considerations while the Australian one may prioritize other environmental factors.

The challenge is that materials have to be incorporated in the code or show that they meet the code requirements to be used in certain applications. Changes and updates to the code occur infrequently and at different times in each jurisdiction adding bureaucratic delays to the adoption process.

This can be overcome by working with the International Code Council (ICC).

The ICC is an independent standard organization and the leading source and creator of ‘model codes.’ These are standardised building code templates which jurisdictions can adopt and adjust to their context. For example New Zealand and Australia may adopt the same model code and then the former would add earthquake considerations. Using this saves governments time and money.

For green material startups this is a boon as the ICC has an ‘Evaluation Service Reports Program’ which is a pathway for new materials to be added to the code outside of the standard government updating frequency.

Going through this pathway means, if successful, the material will be deemed as being code compliant in the US with minimal delay. For a fee, the ICC will guide you through the process (ICC checklist here).

It’s important to note that this process is not seamless and a significant source of risk for startups is the ‘Acceptance Criteria.’

When a material is added to the code, it has to be tested and checked to meet minimum mandatory standards. If the code does not have any clear requirements (which is likely for new material categories), the ICC works to develop ‘Acceptance Criteria’ to perform product evaluations against.

To develop this criteria, the startup, as the expert in the field may be provided with the opportunity to draft these requirements.

These are then presented to an Evaluation Committee, made up of code officials who volunteer their time, for approval.

Certain incumbents have been known to attempt to ‘stack’ the committee in product categories where they are dominant. During the ‘Acceptance Criteria’ approval process they may argue for more stringent testing requirements in the name of safety or risk. These tests may be more expensive and difficult for startups to afford.

If a startup successfully navigates the Evaluation Service Reports Program they will receive an Evaluation Report.

This means your product is now proven as compliant with the building code by regulators and construction professionals in the United States and is an important step for approval for use on site by clients / GCs.

Step 3: Get an Environmental Product Disclosure (EPD)

When delivering a green material, startups need a way to prove that they are, in fact, green to prospective buyers (whom are usually paying a ‘green premium’)

This is done so by provision of an Environmental Product Disclosure (EPD). It’s a third party certification which quantifies environmental information over the life cycle of a product.

It is currently the only tool which can be used to give evidence to a claim on the environmental performance or impact of a material and is required due to:

Regulatory need

For example, the Buy Clean California Act mandates state projects to only use construction materials from suppliers that disclose their greenhouse gas emissions.This information is disclosed is via an EPD.

Similar regulation is expected throughout the US & EU.

Asset Owner reporting requirements

Publicly traded companies have investors such as pension funds which are required to report on the climate performance of their portfolio. They require EPDs for reporting.

It is important to note that an EPD is a point in time measurement. When you provide data for your EPD will impact the measured performance.

For example, startups will get their first EPD during the pilot stage. At this stage their environmental performance is ‘worst’ as they are using 3rd party equipment and have no economies of scale. It is important to highlight to asset owners / investors that these values will improve as they scale and control the means of production.

Additionally, creating an EPD can be a complex and costly affair. There are startups such as Pathways and Emidat which integrate into companies data stacks helping them to easily generate EPDs and update them as their production facilities scale.

For example, if you change a piece of equipment to a lower emission alternative, you’d want to immediately update your EPD to showcase to clients. Traditional EPD generation via a consultant is often a laborious and costly process.

These startups may also be able to project EPD information and help to show to clients how volume growth will help to improve environmental performance.

Step 4: Get Commercial Insurance

Adopting a new material brings risk to the construction process which asset owners and general contractors may not want to own. As such, they may force vendors to mitigate this by obtaining insurance coverage.

The challenge for a green material is that they don’t always fall into predefined categories offered by commercial insurers. As a result, founders must effectively 'sell' their product to insurance brokers for coverage, who often don’t wish to cover you.

To successfully sell, startups must effectively pitch and explain why they should receive coverage by clearly outlining the risk, how it is mitigated and providing supporting evidence such as:

Evaluation Report (Step 2)

This demonstrates code compliance and verifies that your material meets minimum testing requirements.Environmental Product Declaration (Step 3)

Proves your material's environmental performance.Performance Data (Step 1)

Highlights the reliability and effectiveness of your material in real-world applications.

When engaging with brokers, emphasize any additional benefits your material offers. Climate resiliency is a growing priority as extreme weather events lead to increasing claims.

For example, if you're offering a low-carbon cement that is more durable and waterproof than traditional Portland cement, emphasize how your product will reduce extreme weather related claims (insured losses from natural disasters was ~$140 billion in 2024).

Additionally, remember that brokers often have strong relationships with asset owners and general contractors. If they understand and trust your product, they could become valuable advocates and even sales channels for your material in the future.

Note: In discussions, NFP insurance was mentioned as a forward thinking insurer.

Getting to Site

Now all of the requirements to get your material on site have been completed.

The next step is to prove your unique selling point (improved environmental outcomes) to customers via pilot projects. As a green material startup, there is often inbound demand due to the market's growing desire for better environmental performance. However, not all prospective clients are equipped to work with early-stage startups.

Therefore, it’s crucial to filter and identify the right partner, one who understands your context and the unique challenges of startup products. In other words, they should recognize that you are in a learning process and that scaling will take time.

This ensures that you do not waste your time or your runway. So how can we filter prospective customers?

Step 5: Choosing the right customers / partners

When considering construction companies whom are willing to work with startups, they fall broadly into the following two categories:

True Innovators

Fast Followers

True Innovators are companies that understand what it means to work with a startup and recognize that you are on a learning journey. They are experienced in collaborating with early-stage companies, supporting you through pilot projects, and helping you grow in the long term.

On the other hand, Fast Followers wait for a product to be validated before scaling and deploying it rapidly. They prefer a seamless integration process, similar to working with an established material supplier or subcontractor. If they sense you are still building capacity and are not ready to be deployed across projects, they will often disengage.

In startup terms:

A True Innovator is able to work with a Seed / Series A company focused on finding Product-Market Fit and refining solution implementation.

A Fast Follower aligns more with a Series B company, operating under a Go / No-Go framework and ready to adopt your solution immediately if it meets their requirements.

To identify if a company is a ‘True Innovator’ ask the following questions:

Do you have an enterprise strategy for innovation?

You want to understand if they have global or c-suite commitment for piloting early stage solutions i.e. this is a priority and they understand the need for innovation.

Do you have a dedicated piloting team?

These are people who understand what an early stage startup is i.e how to engage with them and recognize pilots are a learning and iterative process.

What is your process for solution adoption?

Your startup is learning and the adoption process should not be overly bureaucratic. There needs to be flexibility to identify the best method for using the solution on site.

Step 6: Piloting

When piloting solutions there are often two stages:

Proof of Concept

Proof of Value

Proof of Concept

This pilot is a controlled, small-scale trial designed to demonstrate the feasibility of implementing your material as well as showcasing its unique selling point (improved environmental performance) on-site.

Once the Proof of Concept is successful, the next question is: Can this be scaled? This leads to the Proof of Value stage.

Proof of Value

While a material may be successfully deployed in a Proof of Concept pilot, clients need assurance that the solution can be implemented across multiple projects. Additionally, they must evaluate whether the cost of deployment or installation will decrease through economies of scale.

At this stage, startups must determine how best to integrate their material into existing construction workflows. This involves assessing the impact on the value chain in terms of cost and time, while identifying potential risks and costs tied to integration.

Startups also need to carefully consider the design and delivery of their solution, particularly given the uncertainties involved in introducing a new material.

For example they may need to consider:

Do we need to teach designers new calculation methods?

Do we need to provide more training for installers to ensure quality?

To understand this further, let’s dive into a case study.

Case Study: Xframes

Xframes is a startup which produces a demountable building system which uses sustainable timber.

Proof of Concept

In the Proof of Concept phase, Xframes must demonstrate that their unique selling point works. Specifically, they need to prove that the building system can be successfully installed and that the walls of the system are truly demountable.

Proof of Value

The next challenge is scaling the process to deploy across multiple geographically dispersed projects. To achieve this, Xframes needs to understand the stakeholders impacted by the construction process and determine how to support them in the delivery phase. The key stakeholders include:

Asset Owner

The asset owner is investing in a new system with a green premium. They need to clearly understand the long-term value of paying more upfront for the system.

Design Team (Architect / Engineer)

The design team must ensure that the building system meets all specification requirements. Structural checks will be necessary to verify that the system can meet design load.

Subcontractor

The building system has its own installation guidelines, which differ from traditional framing systems. This requires additional training, adding to the overall cost, which will be passed on to the asset owner.

Once the impacted stakeholders and their pain points are mapped, Xframes can address their concerns effectively.

The Asset Owner needs to be made aware at the early stage of the additional cost in terms of design and installation. This helps Xframes pre-filter clients who have a climate mandate and the willingness to pay, saving time and effort.

To streamline the Design Team’s workflows, Xframes needs to make it easy to perform design calculations to check loading as well as assist with the process of material performance inclusion into the technical specification (almost every construction project has engineering specifications, these are developed by the designer and have documented requirements that a material, design, product, or service must meet).

Xframes does this by providing free design guides for architects and software which reduce time and complexity.

Once it is in the specification, the GC can procure the framing and system and provide a submittal to validate that the proposed material meets the design specifications.

To support subcontractors, Xframes has optimized the material delivery and installation process. They manage fabrication, ordering, pre-assembly, and dispatch of materials. Additionally, they support installation by the general contractor, a third-party subcontractor, or directly by an pre-approved installation team contracted by Xframes.

The latter option is particularly interesting. In the early stages of market entry, material startups can "self-perform" installation services. This approach allows them to better understand the process and pain points, while also controlling installation costs and ensuring quality (without incurring additional training premiums).

Once the startup has a self-performing team, they can train third-party subcontractors to deliver the building system. Subcontractors may be incentivized to participate in this training because they can become “preferred/partner suppliers” for the material. As partners, they would receive leads and job opportunities, while the startup ensures installation quality for clients.

This partner network model has been successfully applied in the climate tech and repair sectors, as seen with companies like Vamo and Homee.

By using this approach, startups can grow in an "asset-light" manner, leveraging a flexible partner network (rather than in-house installers) that ensures installation quality at a standardized cost.

Case Study Takeaway

When operationalizing the delivery of your material on projects, it's valuable to map the stakeholder personas and understand how your process will impact each of them. Where possible, aim to minimize the impact in terms of time and effort on each persona.

Key personas to consider are:

Asset Owner

They have to pay for the solution.Design Team

They have to validate and ensure materials meet design loading.General Contractor

They have to prepare submittals relating to the material data.Subcontractor

They have to install the material.

Another important question to consider is, is there a single client or location where you can train workers and implement the process on a broader scale?

For example, in Victoria, Australia, the majority of pavement designs used to be completed in-house by the road regulator (although this has since changed). If your green cement startup had trained this team in how to design the solution into their specifications, it would support statewide adoption as their specifications often serve as the baseline or model (similar to the ICC in Step 2).

Step 7: Scaling your commercial facility

At this point in time you have entered the market, proven your unique selling point and understand the design and delivery of your solution.

Now you want to scale.

To do this you may want to build your own manufacturing facilities which will allow you to improve capacity, control quality and improve your environmental performance (and EPD).

To de-risk your investment and secure project financing (and even venture funding) you want offtake agreements.

This is where a buyer agrees to buy a portion of your future output for a guaranteed amount of time ie. I will buy 10,000 tonnes of cement annually for the next 5 years.

You can show the offtake agreement to lenders who, once seeing the proven demand, are more likely to provide financing at more favorable terms. Once you have an offtake agreement, secure intake agreements (offtake agreements with your suppliers) to control future input costs.

Additionally, to maximize the value of your facility you want to widen its market as much as possible. That means your product should be able to be packaged and delivered nationwide or globally.

Having a larger delivery footprint means that you have a wider pool of potential customers and can consolidate demand and offtake agreements improving your financing possibility.

Addendum: Should I take money from Corporate Venture Capitalists?

A question that is often asked is should I take investment from large material suppliers’ corporate venture capital (CVC) arms.

Having a big player on your cap table can help open the market and facilitate introductions and deployment of your material on projects. Some startups have recommended bringing in multiple CVCs to avoid competitive tension and ensure that no single investor has an outsized influence on the company direction.

If you are going to take on a strategic investor, consider if they should have unique controls or rights outside of those granted to normal investors. For instance, some strategies may ask for a Right of First Refusal to buy your company which can impact your acquisition value.

Note: This wasn’t discussed with many startups as it was not the focus of the report, however it was mentioned a few times. Strategics invest for a variety of reasons from wanting to influence the company to wanting to be in a position to acquire. I’d recommend talking to other founders and asking how they structured their cap table.

What’s next?

This article serves as a pathway for green material adoption in construction. It is important to note that it is a living document which will be updated based on feedback and learnings.. It currently ends at Step 7 (and is quite light on details here!) as the startups interviewed were still navigating this section.

If you have any questions or want to chat, please reach out!

Thank you again to everyone who was kind enough to take the time or facilitate introductions for this report.